Every 4th grade student in public school in California studies the missions and related history as part of the curriculum. Part of the lesson even requires the building of a diorama depicting one of the missions. I might know a little more about the missions had I gone to elementary school in California but it’s doubtful. I didn’t tend to my lessons like I should have back then which is probably the reason that the only thing I remember from 4th grade is being on the wrong end of Mr. Barton’s paddle for two, eye crossing and extremely embarrassing swats. Today you would be doing time in a penitentiary for that kind of discipline on a 4th grader; but it worked on me – I didn’t want any part of four swats next time around.

I thought I’d take a couple days and see all 21 missions from San Diego to Sanoma, but after visiting the mission in Ventura I realized that there was NO WAY to get to all 21 in two days. So, I started locally, and went north, visiting missions along the way. I have enjoyed doing my research, and although I don’t know all the details, I do have a general knowledge of the mission system and the time period. Time to get on the bike…

The San Fernando Mission has been totally rebuilt with nothing remaining of any of the structures but one. This is the Convento where the clergy was housed and although it has been through a couple of restorations, it’s still the original walls. It’s the only two story adobe building in California and the largest adobe building in the state as well.

The adobe walls of the Convento at the San Fernando Mission are four feet thick.

Along the Camino Real between Santa Barbara and Buelton

El Camino Real connects all 21 of the missions and is translated as “The Royal Road” or even “the King’s Highway”. The romanticized version of the route is that while driving on the El Camino Real your tires are tracing the same path as the missionaries’ sandals. Tradition has it that the padres sprinkled mustard seeds along the route in order to mark it with bright yellow flowers – here is the rest of the story. It is marked every mile or two along the way by these bells; you’ve probably seen them on the 101 highway north of Los Angeles. The bells used to be made of iron but these days they are made out of concrete to discourage theft – people continue to steal them though. If you would like a “real” bell the company that made the originals will be more than happy to sell you one. El Camino Real Bells Okay, enough about this road and the bells on it.

Father Junipero Serra with one of the Indian children indigenous to the area.

Most of the missions I visited have a statue of Father Junipero Serra. In 1768 he was appointed superior of a band of 15 Franciscans for the Indian Missions of Baja (lower) California. The Franciscans took over the administration of the missions on the Baja California Peninsula after the Jesuits were forcibly expelled from New Spain by King Carlos III. In 1769 the Spanish governor decided to explore and establish missions in Alta (upper) California. The missions were primarily designed to convert the natives to Christianity. Other aims were to integrate the neophytes into Spanish society, and to train them to take over ownership and management of the land. The Indians learned agriculture and construction skills and started building the missions and living in and around them.

the Old Mission San Buenaventura

In the courtyard with a kneeler in front of the statue and flowers and candles all around.

I have literally driven and ridden by Old Mission Buenaventura several times & while I knew it was a church, I never realized it was one of the California Missions. My Catholic roots run deep, and the beautiful statues and chapels take me back in a way that nothing else can. Like many of the missions, the chapel here is still used for Mass. Inside the chapel it’s a little dank but that adds to the authenticity. None of the lights were on so it was lit as it would have been.

It was really dark in here – this exposure, taken from the first pew, was two full seconds.

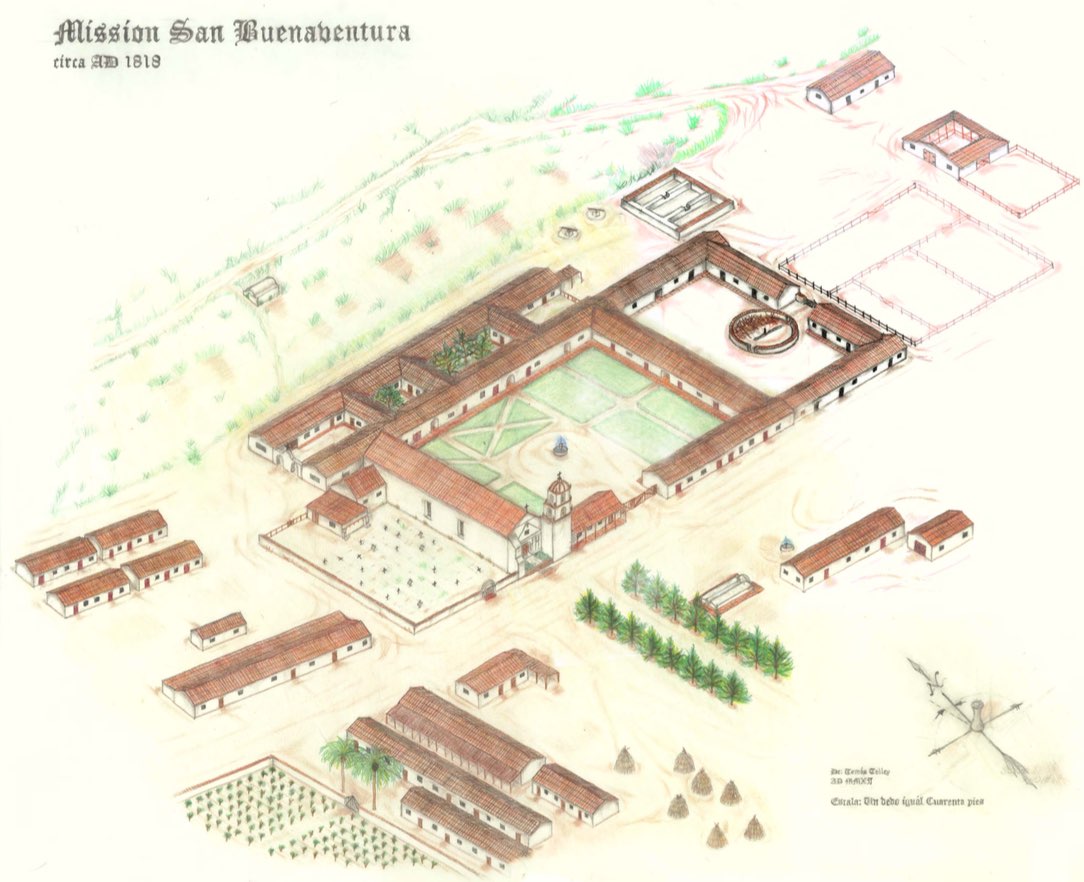

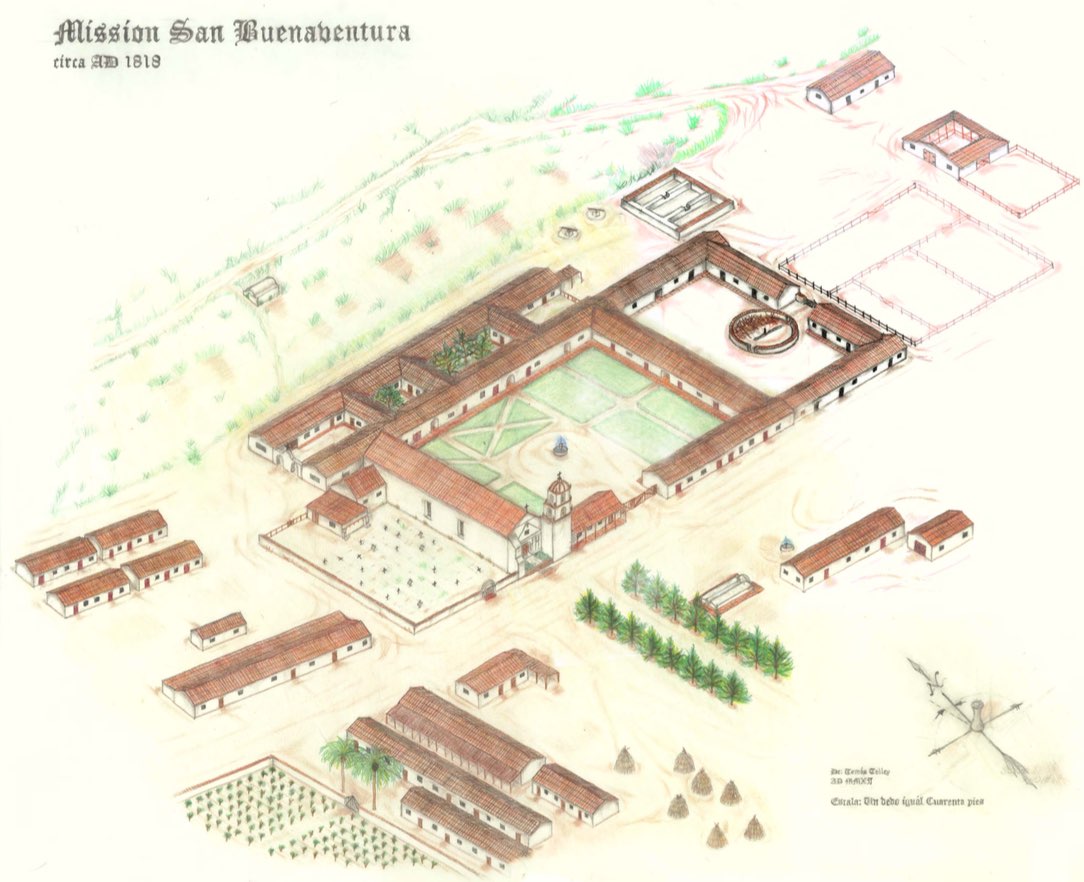

The way it looked in 1818. Now what’s left is in downtown Ventura.

The ride northbound on the 101 is a familiar route. There are other, more preferable, ways to get up the coast but if time is any factor at all, you gotta get on the slab. It does go right along the coast though so at least it’s scenic, and traffic was almost nonexistent. I got off the slab at my earliest opportunity and stayed off for as long as possible. One of the best parts of this ride was seeing the positive effects of our recent rain.

The hills that are normally brown have started turning green, almost looks like Hawaii.

Called the Queen of the Missions for it’s beauty, the Old Mission Santa Barbara lives up to it’s moniker. There is a nativity scene in front of the Mission complete with donkeys, sheep and goats, but there is no baby Jesus. After all, he hasn’t been born yet; on the night of December 24th, he will be there.

Breathtaking inside the chapel, you could easily spend a whole day at this Mission.

Old Mission Santa Ines – Mass is being said, Shhhh…..

Obviously I didn’t make it inside Santa Ines, so I got this picture of the alter off the Internet.

It’s a short ride from the Santa Ines Mission to Old Mission La Purisima Concepcion. If you’re interested in what Mission life was really like, this is where you need to go. It’s a California State Historic Park and after a nominal admission fee you will be walking a little. I didn’t take the free guided tour, but I will be definitely be taking it in the near future when I come back. I know I missed a lot just walking around.

The grounds and buildings at La Purisima Concepcion are among the most complete and authentic Spanish Mission restoration projects in the West.

Inside the chapel at La Purisima. Services are only held here once a year on Founders Day so no problem getting inside for pictures. When the restoration was done they made new adobe bricks and built the place like it was done originally. I’m sure there’s some rebar here and there to ensure earthquake survivability.

Inside the chapel at La Purisima. Services are only held here once a year on Founders Day so no problem getting inside for pictures. When the restoration was done they made new adobe bricks and built the place like it was done originally. I’m sure there’s some rebar here and there to ensure earthquake survivability.

What was left of the living quarters before the reconstruction.

The porch was a gathering place.

Three of the pillars from the building above were used in the restoration and are the only original part of the reconstruction. Adobe bricks kind of melt away when exposed to water so when the roof starts to leak the building is doomed.

Many forces worked together to bring an end to the mission system. The missions had served their purpose as the primary means of “settling” California. By the 1830s the missions controlled about one third of the land that would become California, and the total population In the missions, presidios and towns that were formed had grown to about 30,000. Also, the ever increasing settlers came to covet the lands and property of the missions.

California became part of Mexico in 1821. There was considerable support in Mexico City to end the mission system and the control of these valuable properties by the Catholic Church. Finally in 1831-32 the missions were “secularized” by the Mexican government. Land was distributed to the Indians (most of whom were quickly hoodwinked out of their holdings). The major beneficiaries were former soldiers, settlers and others with influence that were given large land grants. Many of the former mission churches became parish churches but some were abandoned and the Indians largely dispersed into the towns and ranches, or moved to the interior.

My plan was to go to more of the missions, and I will at some point but this post is long enough already and I want to get it published before Christmas. So I’ll leave you with this: